By Dr. Pat Keyser

In working here at the University of Tennessee’s Center for Native Grasslands Management (for nearly a dozen years now), I have focused on trying to develop a body of research that addresses two basic things – how native grasses work in forage production systems and how wildlife respond to them in that setting. Both issues are important from where I sit. If they have no value to producers – as a forage, not as a conservation tool – then it really does not make a great deal of difference how valuable they may be for wildlife conservation. No one will use them. On the other hand, if they produce great forage, but have little or no value for wildlife, then the conservation community may need to look for other places to spend its energy.

On the forage side, we have done a great deal of research, published that research, and have made the results available in popular formats including technical bulletins, web blogs for our Beef and Forage Center, articles in forage trade journals, a large number of training sessions for professionals, and workshops for cattlemen. My goal in all of this is to be sure the forage community understands what native grass forages are, what they are not, how to best integrate them into existing production systems, and hopefully, to de-mystify them. Really, if we can get folks to simply look at them objectively as another forage tool – with their own strengths and own weaknesses – we will have done ourselves and forage producers (in MHO) a good turn. And for the conservation community, this same information will hopefully help us to understand their role more clearly and provide landowners with better information.

Needless to say, this is a long journey. And unfortunately, as I have told many of you through the years, I often encounter cultural resistance to the idea of native grass forages. Maybe it’s like trying to convince a setter man to run pointers, or a Vols fan to pull for Bama? Whatever it is, it can be disheartening. Part of that long road. At other times though, it can be encouraging, when things seem to come together, when there are signs of progress.

Here is a brief story about some of that progress – small steps

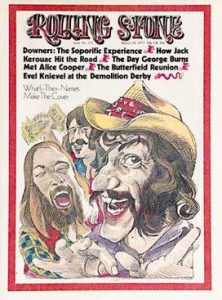

along the road. Maybe some of you are old enough to remember the song about the “the cover of the Rolling Stone,” a strange song about a band that figured they would have arrived, had finally made it, if they could only get their picture, you guessed it, “on the cover of the Rolling Stone” (for all of you young punks out there who have no idea what I am talking about: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Ux3-a9RE1Q – 8.9 MM views to boot!)

So when I got an email with a piece on native grasses forages as the lead story of an e-version of a major forage magazine recently, I figured maybe we had finally arrived. Not seriously, just a stray thought in my mind. But how that story got to this magazine is interesting.

In June, I hosted a professional meeting attended by forage Extension and Land Grant folks across the southeast – a meeting that moves around from state to state each year. As the host for TN, I got to plan the full-day field trip. After having been deep in the Bermuda/Bahia belt for the last 4-5 meetings, I decided I would give them a pretty good dose of native grasses. After all, it was what I have been working on and I have seen very little (none?) of it on the tours those other states have hosted. So we visited several native grass grazing projects and the feedback was very positive. I think these 70 or so forage professionals really enjoyed seeing something different, something they were not that familiar with.

One of the attendees on this tour was the editor of the previously mentioned forage magazine (~40,000 subscribers, mostly serious, innovative, forage growers) who ended up doing two stories based on the conference. One was based on the research that one of my PhD students (Kyle Brazil, a former NBCI team member) is working on – grazing native grasses and grassland birds – and the other on a producer who has been managing switchgrass pastures for several years. (Both articles are posted at http://nativegrasses.utk.edu/manage.htm under ‘Current Articles’.) It was the second one of these that had been sent out on the email version of the magazine. So not only did 70 forage professionals get first-hand exposure to native forages, but two articles were mailed to about 40,000 folks likely to have more than a passing interest in this subject. Not a bad day!

But the fruit from that conference and tour seems to keep coming. Another attendee at this meeting was a colleague from Mizzou. He was interested in our work, enough so to invite me out to Columbia to conduct a seminar on campus that was attended by most of their forage team. That seminar generated some great conversation and I think, gave some of these folks who have worked in fescue for years some food for thought.

As a side benefit, I got to visit Linneus (Mizzou’s main forage research area) where I got to see the three NWSG pastures they established last year in support of a grazing project proposal we have been collaborating on (an exercise that resulted from my trip out to the Mid-MO Grazing Conference back in 2013 when I set up a side meeting with their main forage researcher).

While at Linneus, I was able to spend a good deal of time with their station manager discussing NWSG forages/management (we will be in very good hands there if the project is able to move forward!). In addition, my faculty host and I conspired to start some native grass forage research at the Beef Unit there at Columbia, work that appears to be moving forward with some help from MDC. Also, as a result of this initial visit, I have been invited back this winter to conduct an in-service training with all of their forage and beef agents.

Like most of you, I seem to spend most of my days stubbing my toes, tearing out my hair, and going through various cycles of despair and hopelessness. So it’s kind of nice to see things work out like this. I guess this is the way we hope this whole system would run. But regardless of the ups and downs, the successes and failures, the road back to a world where native grasses can play a role on our farms is a long one, one that will be traveled one step at a time.