Author’s note: I got long-winded again. I guess I could have used 40 mimes, or 100 tweets to try to convey this, but I am old school. I write for people who still like to take a few minutes and read. I have been lucky to spend the last 24 years involved with some of the best quail researchers in the world and also some of the best people. Here are a few recollections of that time.

I gave a talk to a distinguished group of local landowners and bird hunters last Friday evening at Lowry’s Restaurant in Tappahannock, Va. It’s one of the few places I know of that has “all you can eat” deep fried quail on the menu. I can’t say I ever saw so many farm raised quail consumed in one sitting in my lifetime (I had a turkey sandwich – you ever try to eat fried food before giving a talk?). It was ironic my talk was on quail nutrition, since quail were the nutrition of choice that evening. I began my talk with this statement: “You can learn a lot about quail by hunting them behind a good bird dog, but there is a lot you don’t learn that way, too.” Lately I have looked back over what I term my “quailucation” – my quail education, and I realize it has been a pretty darn good one.

It was as a kid rabbit hunter back in Pulaski County, Virginia that I first started to develop a search image for what gamey cover was. After a few years of chasing bunnies, even a boy gets to know where not to waste time. I recall a number of quail coveys flushed in those pursuits and I can see them all flying away as clear as a dew drop to this day. Many were using “old home sites.” There were sagging fences, overgrown with brambles, old hog lots with rich dirt and diverse plant life, and collapsing cabins whose old yards could hold rabbits, quail and even grouse. I’d have laughed in any person’s face back then who said to me “That’s good early-successional habitat.” What!? It was just thickets and brush to us. And there was a lot more of it then, along with chinquapins, bumble bees, butterflies and migrating birds (and a lot fewer of us).

Later in life, when I was about to complete my undergraduate degree, a good friend of mine saw me walking down a hall at Virginia Tech and he had a flyer in his hands. He said to me “Marc, you ought to put in for this project on quail in North Carolina.” I’d always wanted to be a bird hunter, but had never figured it out. I took him up on the idea and long story short, I ended up being accepted to North Carolina State University working under the tutelage of Dr. Pete Bromley and in close concert with Bill Palmer, now CEO of Tall Timbers Research Station.

Dr. Bromley made me a professional and Bill made me a bird hunter…along with Frank Howard, a tobacco farmer and “old time” bird dog man of great ability who battled Parkinson’s disease as he shared his knowledge of bird dogs with us. I did not realize then how lucky I was to have these three men continuing my quailucation. Frank told me once, “Marc, I have trained enough bird dogs in my life, if you hooked them all to a harness, they could pull a 747.” I began to learn quail from several new angles. I saw how quail behaved when surprised. I began to learn when, where and what they fed on. I learned how they called to one another, and also how to stay very quiet in approaching a dog on point, so quiet you could sometimes hear the soft calling of the quail and be a little less surprised at where they flushed. I learned that in some circumstances they’d hold so tight they’d literally come up between your legs, and in others they’d run ahead and come up out of range. And I began to see why…the closer you came upon them before surprising them the tighter they held. They can hear as well as turkeys.

Simultaneously, I began attempting to trap quail for my research project. My study area was the contract farming units on the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge in the coastal plain of North Carolina. My first few weeks of quail trapping were a lesson in humility. I had trapped a lot in my youth, but I found catching quail to be more difficult than trapping raccoons, muskrats and foxes.

Quail don’t rely on their sense of smell to locate food, thus they cannot be lured to a trap with scents. I started to realize that you had to put the traps where the quail were…not 10 feet away from where they were. I learned how they “stage” in edge thicket cover before moving out to feed. And it was in these staging areas that they could be captured with some success. I also learned their affinity for shrubby cover and brier thickets. If I was not battling thickets when setting traps, I caught few quail.

Something else I noticed was that they did not always walk to where they wanted to be. I witnessed on more than one occasion their flight to a feeding area and then back to cover. These flights were fast, only a few feet off the ground and in complete concert with one another. Up in a split second, buzzing out to the feeding area, and then after feeding quickly up and back into cover in a matter of seconds.

One morning as I was hunkered under a blackberry thicket re-setting a trap, a covey flew into the thicket within 10 feet of me. I lay still and listened. They were calling softly to one another and they knew something was amiss. I listened for a time and then started sliding my way out of the thicket. I managed to get out without flushing them and I later caught that covey. I had found their covey headquarters for sure.

Something else I saw them do on more than one occasion…just at dusky dark, they flew out into the wide open soybean stubble fields to roost. I confirmed it by looking for their roosting disks during daylight. I suspect in their case, if not spotted by an owl, they were safer out in the stubble than along the field edges.

The quail were especially difficult to catch on one portion of the study area. It was wide open and windswept, and the only cover existed along drainage ditches. Bill Palmer visited almost weekly, as my study was nested within his larger study. He was depending on me to catch quail. We were both perplexed by this section and then Bill had a spark. The wind brought the Northern Harriers, and the harriers cruised those ditches back and forth all day long. The only place the quail felt secure was down in the big drainage canals at the end of each field.

So down we went, excavating trapping sites eight feet down the steep banks of those canals. I later borrowed a canoe from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and put in at one end of the canal. It was still cold so no worries about gators or moccasins. And, low and behold, as I canoed around these canals I gave many a quail their first glimpse of a human in a canoe. The look of surprise they exhibited as I came up almost eye to eye with them was priceless. But they held tight as I paddled by. This was a lesson for me in their adaptability.

I later also learned how nature interacts. The harriers came for meadow voles, not quail, and when the vole population crashed the Harriers did not tarry. Low vole populations meant less harassment for the quail of ARNWR. We also found that incorporating field borders along drainage ditches running through crop fields helped quail, but were not a complete substitute for larger blocks of fallow land. Ideally, farmed landscapes will incorporate a variety of fallow fields and borders, and maximize “weedy areas” whereever possible.

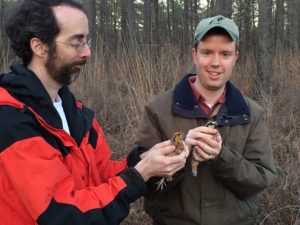

During those days we also raised quail in captivity and hatched eggs, thousands of them. Other students were studying different aspects of quail ecology offering more learning opportunities. We ran sweep nets for insects to feed the young quail. What predators they are! To observe their foraging habits, many were imprinted on humans after hatching, and it was a fun sight to see a student walking along “cheeping” at the little quail as they fed. Grasshoppers, crickets, beetles…they jumped on them with a raptor’s zeal. In one case a chick grappled with a praying mantis as large as it was and was unable to kill it. If you look at a quail chick up close, its head is all mouth. The shape of their young mouth reminds me of the nightjars (Chuck-Will’s- Widows, Whip-poor-wills, nighthawks, etc.) which have such large mouths for night foraging on insects.

Upon coming to Virginia I was lucky to work with several more fantastic people: The “Old Timer,” Irv Kenyon, who wrote “Beyond the Foodpatch” and had forgotten more about quail than most people will ever know; Steve Capel (our leader, now retired but still going strong for habitat); Patty Knupp “Sister” who kept us all in line, now with NRCS in Colorado; and Mike Fies who was responsible for some of the best research ever done on quail in Virginia or elsewhere. In conjunction with NCSU researchers, we helped study predator effects, translocation of bobwhites (back before it became “new”), survival of pen-raised quail, and more.

We found that predator control only made sense if a person had first invested in fantastic habitat, and then if done, it had to be done every year. The best dollars spent are on habitat first. We found that translocated wild bobwhites did survive much longer then pen-raised quail, averaging 39 days versus the 2 to 3 for pen-raised, but there was no substitute for managing habitat to produce locally hatched and raised wild quail. We found that having a quail brood is tough on the parents, with 39% of the hens hatching eggs dead within 40 days.

And we set up remote cameras on hundreds of hatched or depredated quail nests. This led to close to 5,000 photographs of nest depredations. We found that raccoons, opossums, skunks and foxes were the main culprits. Out of all those photos we had one case of a deer eating a quail egg, one groundhog and a couple crows. We never had a single photo of a turkey depredating a quail nest. Or a coyote.

Before we did this study many people assumed that if you found a quail nest with all the eggs gone and no broken shells or other evidence, then it must have been a snake that ate the eggs whole. Not so fast! We also used remote video cameras and guess who else steals eggs leaving no trace? Mainly red foxes – we assume they carry the eggs off to feed young, or cache them for later use.

Research over the years has also shown many surprising things about quail. They move more than once believed. We found quail after losing a nest to predators almost always moved a long distance, 1,000 yards or more, before re-nesting. Studies in Oklahoma found a covey moving over 100 miles in fall. I saw quail in Virginia move almost a mile in a single day (they do know how to fly). Though many stay close to home, enough move to help keep genetic diversity alive even at low densities. We also now know that monogamy, once thought to be the “norm” for bobwhites, is not the case. As many as 25% of quail nests are incubated by males. Some hens leave nests with males and go have another nest. There is a lot of mixing and matching going on in “quaildom.”

We continue to try to stay on the cutting edge of quail research. We have been fortunate to have had Dr. Theron Terhune, Tall Timbers Game Bird Research Coordinator, visit with us multiple times, as well as Dr. Chris Moorman, Wildlife Unit Leader at NCSU, another fine quail program with ongoing research into quail ecology.

For those who may not understand the job of a state species project leader, one big aspect is to stay current on recent research on your species. I believe we are doing that in Virginia. We have not let “moss grow.” I continue to read every wildlife journal and newsletter I can find to insure we do not fall behind and grow stale. We continue to look for opportunities to start new quail research. Dollars have been tight for it, but we hope to continue to look for funding so that we don’t fall into the trap of thinking we know all there is to know about any species. Conditions change, species change, and we are either learning more about them, or we are falling behind. We have a new quail team now full of bright, enthusiastic biologists who are making their names known and we continue to strive to do our best for Virginia’s quail.

Happy Thanksgiving to you all!