2015 was the International Year of Soils and the fervor over cover crops that resulted still continues today. It seems every time I turn around I’m seeing another notice about a workshop or webinar addressing cover crops and their benefits.

Though the line between fact and commercial claim is somewhat blurred, it is generally recognized that cover crops provide the advantages of reduced soil erosion, increased water infiltration and water holding capacity, increased soil organic matter, reduced compaction and nutrient recycling.

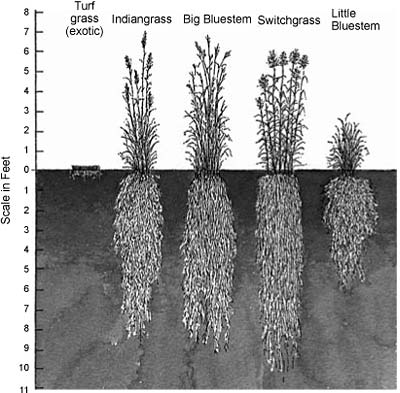

To a large part, owing to their multiple benefits, is their claimed deep rootedness. With many of the common cover crop species, their roots fall within 2 to 3 feet of the soil surface, with some

reporting rooting as deep as 5.5 feet. Impressive to the uninformed, but amusing to those familiar with the roots of native vegetation.

As early as 1919 research of the roots of native prairie plants was conducted, followed by a number of other research projects through the 1930’s. While there are a handful of prairie plants whose roots lay within the upper 2 feet of the soil, the vast majority of native grasses and forbs root to a depth of over 5 feet with many well beyond that, some to depths greater than 15 feet.

In healthy prairie, below ground biomass far exceeds above ground biomass by two times or more depending upon species. Studies on big bluestem and little bluestem reported 5.4 tons/acre and 4.4 tons/acre respectively of root material in the upper 12 inches of soil. Talk about erosion control … every one of those root fibers is like re-bar in concrete!

All of those roots in the upper soil lead to increased water infiltration by increasing the macropore space (along with earth worms and other in-ground fauna), allowing the water a route to travel into and through the soil. Those roots and their ancillary structures also increase the micropore space which creates the water-holding capacity along with soil organic matter.

Over a three year period, depending upon the species and environmental factors, a very small percentage to as much as 100% of the root system dies and is regenerated. Using 50% just to provide an example and the examples of big bluestem and little bluestem above, 2.7 to 2.2 tons per acre of organic matter are added to the soil. It is a perpetual cycle that constantly replenishes itself.

The sources of compaction on native grasslands are entirely different than on cropland, thus the issue is different; however, when crop land is converted to native grass/forb mixtures, compaction issues are eliminated, or at least significantly mediated, through the deep rooting structure of the native plants.

A large part of the nutrient recycling provided by cover crops is due to nutrient uptake and subsequent release through decaying plant material. In a perennial plant such as native grasses or forbs this is much less significant, but the deep roots are able to tap into nutrients otherwise unavailable. This, in combination with associated mycorrhizal fungi, make native plants very efficient users of nutrients and moisture, thus their reduced or lack of need for supplemental nutrients and drought tolerance.

Following the International Year of Soils and all the attention given to cover crops, give some consideration to the value of the roots of native vegetation and their role in supporting soil health.