I believe most of you are at least somewhat familiar with fescue toxicosis. I was prompted to blog about it because of the time of year. Over the past several weeks, driving around during my daily activities, I noticed tall fescue seed heads emerging and cattle grouped under shade trees and in ponds — all three visual reminders about fescue toxicosis.

There are an estimated 35 million acres of tall fescue in the United States with as much as 85% of that infected with the endophyte fungus. An examination of fescue pastures sampled in Virginia in 2013 showed 95% were greater than 80% infected (incidence of the endophyte), with the lowest being 50% infected. Fescue toxicosis is estimated to cost US beef producers more than $2 billion annually in losses.

For those unfamiliar with fescue toxicosis or a brief refresher for others, cattle grazing endophyte infected tall fescue, compared to those not, exhibit reduced weight gain, reduced pregnancy rates, reduced milk production, lower weaning weight calves and reduced reproductive efficiency in bulls. Conditions that cause these symptoms are immunosuppression, vasoconstriction and poor thermoregulation.

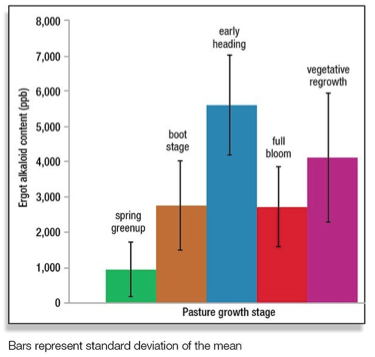

The endophyte fungus is greater in the seed stalks and seed heads than in other plant parts so impacts on grazing animals are greater during this time of year; and this, combined with reduced forage quantity and quality during the late spring and summer months (remember the cool-season grass growth curve?) coalesces into poor animal performance during the summer. Recommended pasture management when seed heads emerge is mowing to remove their availability to grazing. However, in the same Virginia research mentioned above, alkaloid (alkaloids are the class of compounds produced by the endophyte fungus that causes fescue toxicosis.) concentrations were above the reactionary threshold level regardless of pasture growth stage or grazing management.

Therefore it did not matter when or how you grazed your endophyte infected tall fescue, it had the same impact on the animals. You can’t manage around it.

Experts do agree that you can dilute the intake of infected tall fescue by diversifying the planting … adding clover, orchardgrass, timothy or warm-season forages, but you don’t eliminate the effects of fescue toxicosis. Even then, you don’t address the slump in cool-season production during the summer months, with the exception of using warm-season forages.

The most effective way to eliminate fescue toxicity is to eliminate all toxic alkaloids from the animal’s diet and that is a practice many farmers and ranchers are undertaking today. Their option is to replace it with endophyte free, novel endophyte tall fescue or other forage that doesn’t carry the endophyte fungus. Endophyte free fescue doesn’t compete well with other plants nor does it persist under heavy grazing. As it turns out, the endophyte fungus provides a positive benefit to the plant. Novel endophyte tall fescue has beneficial endophyte fungus, just not one that creates the toxic alkaloids. However, if converting to novel endophyte tall fescue, all of the endophyte infected fescue MUST be eliminated before planting. Thus the recommended method for converting is to graze down the pasture, spray with herbicides, plant a cover crop, graze the cover crop, spray with herbicide and plant.

Guess what? This is the same method recommended for planting native warm-season grasses.

With all the steps being the same, it stands to reason the cost of establishment, for comparison’s sake, is the same except for seed, lime and fertilizer – because those will be different. I recently called a local seed supplier to get the price for novel endophyte tall fescue seed and their recommended seeding rate and a native grass seed supplier for the same information on big bluestem, indiangrass and switchgrass. The following table breaks down the variable costs. Note that it is difficult to make an exact comparison when talking about lime and fertilizer because those inputs are dependent upon the location and the soil test results. Most establishment guidelines recommend lime and fertilize per soil test recommendations, however native warm season grasses don’t need lime unless the site pH is less than 5 and only need P and K if they are measured in the low category. Nitrogen is seldom recommended for NWSG establishment, yet nearly always for CSG establishment. For the sake of this discussion let’s say that the pH is neutral and the P and K recommendations are the same.

|

Material |

Recommended seeding rate |

Unit cost |

Cost range |

N fertilizer |

End-cost range |

|

Estancia Tall Fescue |

20 – 25 lbs./acre |

$3.50 bulk pound |

$70 – $87.50 |

$21.00* |

$91 – $108.50 |

|

Big bluestem |

8 – 10 lbs./acre |

$8.00 PLS pound |

$64 – $80 |

$0 |

$64 – $80 |

|

Indiangrass |

8 – 10 lbs./acre |

$14.50 PLS pound |

$116 – $145 |

$0 |

$116 – $145 |

|

Switchgrass |

4 – 8 lbs./acre |

$10 PLS pound |

$40 – $80 |

$0 |

$40 – $80 |

|

*50 units of N @ .42/unit. (Recommendation of U of K Extension publication; N cost based on call to local supplier.) |

|||||

The Myths

Native grass is too expensive to establish.

The above table fully debunks the myth that native warm-season grasses are too expensive to establish. If you’ve made the decision to convert from endophyte infected tall fescue to novel endophyte, the cost argument is no longer valid.

I lose too much grazing time waiting on establishment.

When converting from endophyte infected to novel endophyte tall fescue there must be a “break-crop” planted in the interim and recommendations are to not graze seedling pasture the first winter; so you are losing grazing for one year. When planting native warm season grasses a “break-crop” is not necessary (though not discouraged either) and with proper planting methods and good weed control, it can be grazed a year later. Assuming the weather cooperates, under either scenario, there is no difference.

Native grasses require more management.

Really? Tall fescue experts recommend not overgrazing novel endophyte tall fescue, in fact you need to be more careful to avoid overgrazing; pastures should be rested and stubble heights should be no less than 4 inches. Native warm-season grass experts recommend not overgrazing native grasses, in fact you need to be more careful to avoid overgrazing; pastures should be rested and stubble heights should be no less than 8 to 12 inches, depending on geographic location. Hmm, sounds the same except for stubble heights.

The Advantages

During the summer months the advantage goes to native warm-season grasses. The summer months are their peak months of quality and productivity, whereas tall fescue, toxic or not, is at nearly its lowest point of quantity and quality. Average daily gains on NWSG during the summer are regularly at or above 2 lbs. per day, much better than tall fescue during this same time period, at 0.5 to 1 pound per day.

Care must be taken to not re-infect an infected fescue converted to novel endophyte tall fescue field. Cattle grazing infected fescue need to be “quarantined” for a day to avoid transferring seed in manure. Also infected hay cannot be fed in a novel endophyte pasture. Once a field is infected, it only gets worse because of the competitive nature of the endophyte infected plant. You have to ask, how easy will it be to find non-toxic hay and how much hassle is it to “quarantine” cattle for a day, knowing that unless it is in a field planted annually, will eventually be infected with the toxic endophyte? No need to worry in a NWSG pasture. If fescue invades, simply spray the field with a non-selective herbicide in the fall or spring while the native warm-season grasses are dormant and the cool-season fescue is actively growing.

We’ve already discussed the problems with animal performance related to fescue toxicosis so know that by removing them from the source of the problem, those performance issues are eliminated. That should be incentive enough but if you still aren’t convinced, the following probably won’t sway you either but it is important to know that NWSG’s improve soil health, water infiltration, nutrient filtration and carbon sequestration, above and beyond tall fescue, toxic or not. Oh and by the way, they are significantly more drought hardy; something producers wished they could have had in 2011 and 2012!

Seems logical if moving away from endophyte infected tall fescue that native warm season grasses should be part of that plan.